ONCE UPON A PAIGE

Living in Earthquake Country

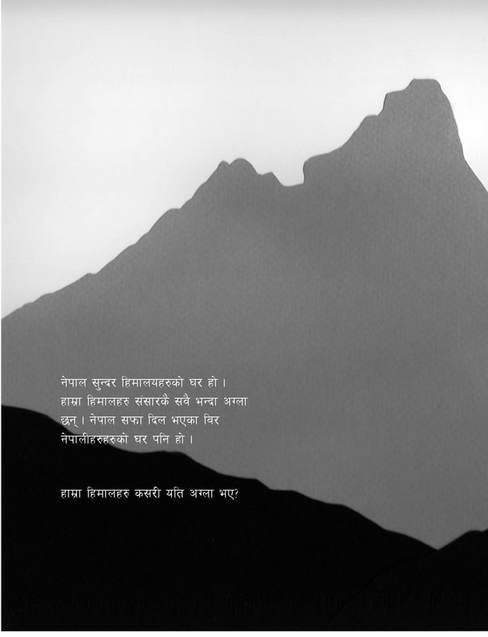

When a terrible earthquake shook Nepal in 2015, levelling exquisite temples and wiping whole villages off the map, the faces of children I’d taught in the Peace Corps decades before filled my mind. Of course, those kids had grown up and were parents or grandparents by now, but I was pretty sure today’s children weren’t getting any explanation for why their world had been literally shaken to the core. I wrote a little pamphlet for them, explaining plate tectonics in simple terms. That led to the logical question, “What are we supposed to do about living in an earthquake zone?”

My friend John Vavruska, another former Peace Corps Nepal volunteer, jumped straight into that practical matter. He was in Nepal within two weeks of the original quake (there were many aftershocks), bringing tarps and food to the village of Chupar, where most of the handsome stone houses had been reduced to a pile of rubble and not a single one was safe to enter. The villagers told John and his companion, Nepali-American Uttam Rai, that their priority was to rebuild the school, and to build it big enough so the children could be taught in the village through the middle grades before having to walk hours to another village to continue their schooling.

John began researching earthquake-safe building techniques using materials available in remote villages, or easily transported to them. Concrete and rebar were off the list, but architect Randolph Langenbach had come up with a technique of building strong walls by tying certain courses of stone together with wire or plastic mesh in “gabion bands.” The lovely new Chupar school was built using gabion bands. My little book about where earthquakes come from turned into a simple guide for building a strong house in earthquake country. It ends with a song written by a Nepali friend which has the chorus, “We are the budding plants of Nepal, we have the energy to rebuild our country!”

My friend John Vavruska, another former Peace Corps Nepal volunteer, jumped straight into that practical matter. He was in Nepal within two weeks of the original quake (there were many aftershocks), bringing tarps and food to the village of Chupar, where most of the handsome stone houses had been reduced to a pile of rubble and not a single one was safe to enter. The villagers told John and his companion, Nepali-American Uttam Rai, that their priority was to rebuild the school, and to build it big enough so the children could be taught in the village through the middle grades before having to walk hours to another village to continue their schooling.

John began researching earthquake-safe building techniques using materials available in remote villages, or easily transported to them. Concrete and rebar were off the list, but architect Randolph Langenbach had come up with a technique of building strong walls by tying certain courses of stone together with wire or plastic mesh in “gabion bands.” The lovely new Chupar school was built using gabion bands. My little book about where earthquakes come from turned into a simple guide for building a strong house in earthquake country. It ends with a song written by a Nepali friend which has the chorus, “We are the budding plants of Nepal, we have the energy to rebuild our country!”

Before we could publish, however, the Nepali government established standards for school construction and made funding available for communities to rebuild their schools so long as they were built in conformance with those standards. Our story of earthquakes and the courage and commitment of the village of Chupar to rebuild may be useful as history. We await guidance by a curriculum designer to see how a revised version of the story could be made useful in Nepali schools.